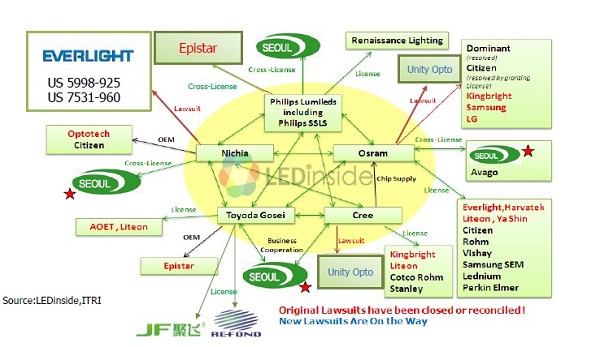

For a long time, Nichia, Osram Opto., Cree, Toyota Gosei and Lumileds have jointly shaped an enormous and powerful patent shield with cross-license agreements within the world LED industry and the five lighting goliaths have been charging, more or less, whoever tried to sell LED products abroad. However, as those patents are about to expire, Taiwan- and Korea-based Companies rise with their new patents and the expansion of Chinese businesses is posing threats, the industry is slowly transitioning away from the old oligopoly.

The Shield of Five Is Weakening

What we commonly know is that most of the patent infringement lawsuits are filed from these lighting giants against companies in Taiwan, Korea and China. In particular, Nichia is the most relentless among them all. In 2009, Seoul Semiconductor joined the squad of five after it peacefully settled a bitter litigation with Nichia. The LED patent market was then manipulated by the six companies.

|

As time goes by, somehow foreseeably, with their businesses gradually going downhill, these patent holders changed their strategies to revamp their businesses by earning licensing revenue or releasing some of their patents. Nichia’s white LED related YAG ‘925 patent, as powerful and invincible as ever imagined, will soon expire on 29th July 2017. In addition, Everlight scored victories declaring Nichia’s lawsuits as invalid cases in a few countries including the United States. That has weakened Nichia’s patent defense. The patent defense of the major lighting companies is crumbling down and the oligopoly in the market might end forever.

Chinese Corporations Reach Out to Overseas Markets

Apart from the aforementioned change, the expansion of Chinese LED companies adds more uncertainty to the post oligopoly era.

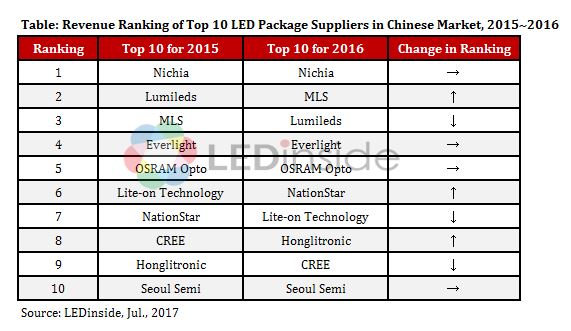

The list of 10 largest LED companies by revenue LEDinside puts here shows that some Chinese firms have made their ways up to the top 10 after their large-scale business expansion which includes the fact that they acquired or merged with international LED companies recently. China Electronics Corporation (CEC) bought Bridgelux in 2015. San’an Opto acquired Luminus in 2013. Refond and Jufei Electronics both earned licenses from Toyota Gosei. All that embodied the ambition of Chinese companies to enter overseas markets. Also, more and more international lighting companies have passed original equipment production tasks to Chinese ones, indirectly increasing their share in overseas markets. The rise of Chinese LED manufacturers certainly threatens the global corporations and those regional companies. More litigations are anticipated to come in the future.

|

Here’s a recent case that well exemplifies that. Early in June, Everlight filed a lawsuit against Bridgelux for some accused products of the CEC’s subsidiary, including the commonly used 2835 LED package. Nonetheless, Bridgelux claimed it owned over 750 patents related to LED chip and package technology worldwide and had a cross-license agreement with Cree. Chinese LED makers surely benefited from M&A deals with overseas companies that may hold more patents and advanced technology. The case also illustrated that companies like Everlight already sensed the change and proactively tailored their strategies to maintain their advantages.

Downstream Companies Can Hardly Get Away

In the face of the change and increasing pressure, Taiwanese and Korean companies accordingly adjusted their strategies in terms of legal action. They make moves first, filing lawsuits against Chinese LED makers with relatively competitive cost structures to secure their positions.

In terms of LED lighting, LEDinside observes that the majority of lighting OEMs still prefer patented LED light sources for their products in order to avoid potential legal issues when shipping out their products to retailers and lighting brands in Europe, America, Japan and other markets that emphasize intellectual property. They would rather purchase LEDs from the five lighting giants despite higher prices, while they might also choose partial LED components from Seoul Semiconductor, Samsung LED and LGIT considering the cost. On the other, Everlight, after a few major wins against Nichia, also obtained favorable reception worldwide with its products featuring Epistar’s advanced chips.

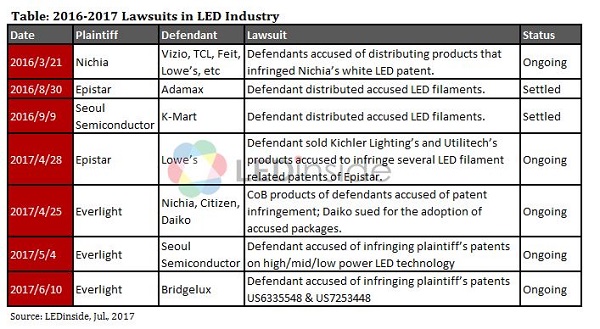

In the past, LED manufacturers never really sued other companies but rivals, but, these days, more and more targets happened to be in the applications sector. They avoided including lighting application companies in the litigations for those companies that purchased LEDs from their rivals could also be their clients. For application companies, ‘a bit of LEDs from everyone’ is one of the strategies to get themselves away with any legal actions as they become clients of multiple LED brands. Yet, Nichia broke the balance in March 2016, charging Vizio, the biggest television seller in the States, with distribution of patent-infringing products. It also accused Feit, TCL, and Lowe’s, which is considered the second largest hardware chain in the US behind the Home Depot, for the same cause. The litigation is still ongoing and, interestingly enough, these accused companies to some extent also use products from Nichia, which just means Nichia filed a lawsuit against its clients.

Others such as Epistar, Everlight, and Seoul Semiconductor followed suit to aim their legal attacks at application companies. Epistar and Seoul Semiconductor both filed lawsuits regarding LED filament patents. Although they have been settled, the litigations for certain delivered warnings to downstream lighting companies. In April 2017, Epistar sued Lowe’s; meanwhile, Everlight also charged Nichia, Citizen and even its own client Daiko, one of the top five Japanese lighting application companies with patent infringement and adoption of accused LED packages. With the number of lawsuits targeting downstream companies on the rise, it remains to be seen whether the tension in the LED chain will ever cool down with the upcoming expiration of Nichia’s white LED patent in 2017 and 2018.

|

LEDinside reckons, despite all above saying the patent shield might weaken and a new dynamic will be formed to replace the old oligopoly in the patent market, it doesn’t necessarily mean the lighting goliaths are losing their edges. Instead, the change might ignite the fire of a new patent war where there’s no companies standing as ‘ultra big and powerful’ but numerous firms with their own patents. By that time, they will be competitive at similar levels. The competition in the market is expected to continue in a different form and the applications sector might as well keep alert to it.