The upconversion of photons allows for a more efficient use of light: Two photons are converted into a single photon having higher energy. Researchers at KIT now showed for the first time that the inner interfaces between surface-mounted metal-organic frameworks (SURMOFs) are suited perfectly for this purpose - they turned green light blue. The result, which is now being published in the Advanced Materialsjournal, opens up new opportunities for optoelectronic applications such as solar cells or LEDs. (DOI: 10.1002/adma.201601718)

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are highly ordered molecular systems that consist of metallic clusters and organic ligands. At the Institute of Functional Interfaces (IFG) of KIT, researchers developed MOFs that grow epitaxially on the surfaces of substrates. These SURMOFs (surface-mounted metal-organic frameworks) can be produced from various materials and be customized using different pore sizes and chemical functionalities so that they are suited for a broad range of applications, e.g. for sensors, catalysts, diaphragms, in medical device technology or as intelligent storage elements.

|

|

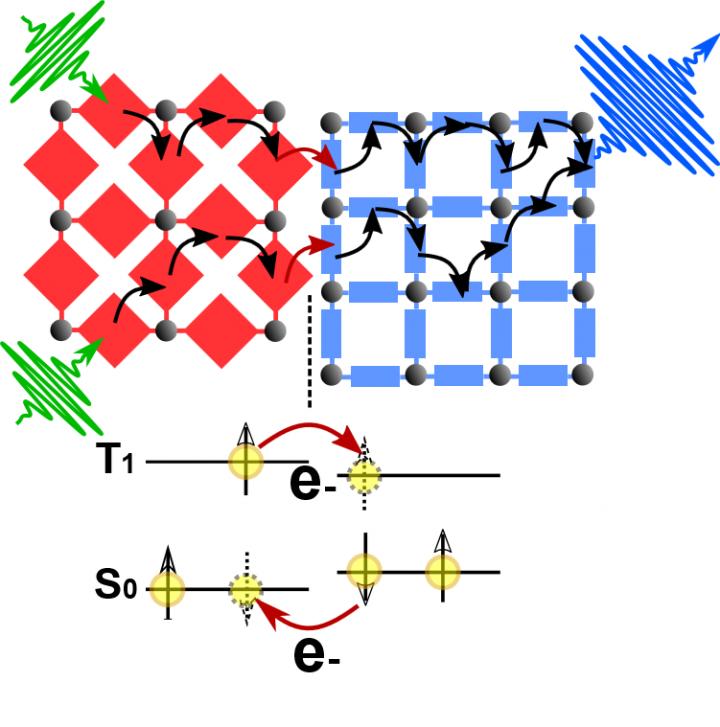

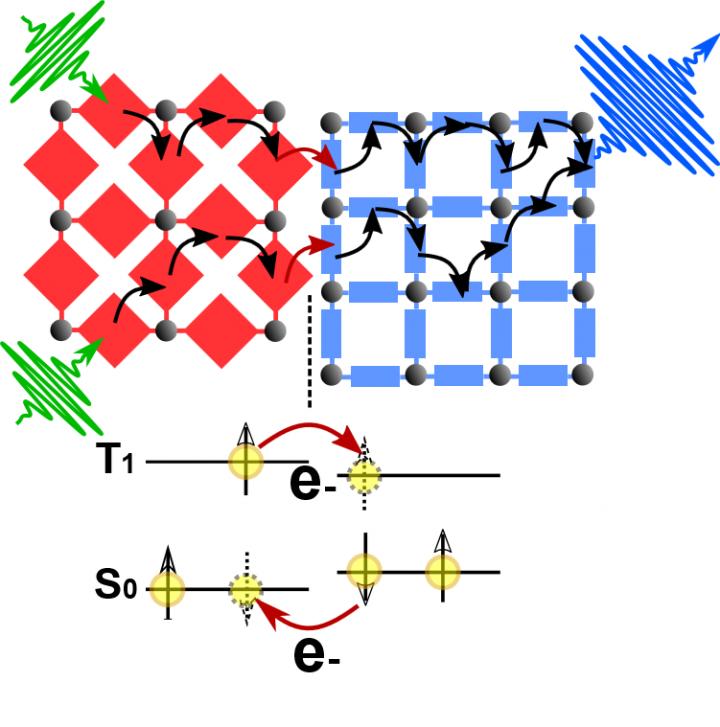

Photon upconversion energy transfer between the molecules based on electron exchange (Dexter electron transfer). (Illustration courtesy of Michael Oldenburg) |

Another field of application is optoelectronics, i.e. components that are capable of converting light into electrical energy or vice versa. Many of these components work on the basis of semiconductors. "The SURMOFs combine the advantages of organic and anorganic semiconductors," Professor Christof Wöll, Director of IFG, explains. "They feature chemical diversity and crystallinity, allowing us to create ordered heterostructures." In many optoelectronic components, a so-called heterojunction - this is an interfacing layer between two different semiconductor materials - controls the energy transfer between the various excited states. Researches of the KIT Institute of Microstructure Technology (IMT) now created a new piggyback SURMOF in which a second SURMOF grew epitaxially, i.e. layer by layer, on a first one. At this heterojunction, it was possible to achieve photon upconversion, transforming two low-energy photons into a single photon with higher energy, by virtually fusing them together. "This process turns green light blue. Blue light has a shorter wavelength and yields more energy. This is very important for photovoltaics applications," explains Professor Bryce Richards, Director of IMT. The scientists are presenting their work in Advanced Materials, one of the leading journals for materials science.

The photon upconversion process shown by the Karlsruhe researchers is based on the so-called triplet-triplet annihilation. Two molecules are involved: a sensitizer molecule that absorbs photons and creates triplet excited states, and an emitter molecule that takes over the triplet excited states and, by using triplet-triplet annihilation, sends out a photon that yields a higher energy than the photons that were originally absorbed. "The challenge was to create this process as efficiently as possible," explains Dr. Ian Howard, leader of a junior research group at IMT. "We matched the sensitizer and emitter layers in a way to obtain a low conversion threshold and a higher light efficiency at the same time."

Since the triplet transfer is based on the exchange of electrons, the photon upconversion process revealed by the researchers includes an electron transfer across the interface between the two SURMOFs. This suggests the assumption that SURMOF-SURMOF heterojunctions are suitable for many optoelectronic applications such as LEDs and solar cells. One of the limitations for the efficiency of today's solar cells is due to the fact that they can only use photons with a certain minimum energy for electric power generation. By using upconversion, photovoltaic systems could become much more efficient.