Well, there’s no question that they’ve changed our methods of design. There are some very positive aspects of LED. One is the idea that we have new form factors that we’ve never had before. So, in architectural lighting design, these new LED form factors allow us to create projects that we never could before. Then, there’s OLED, which is a good example of how sources will challenge us in the future. Controllability is the next aspect – it allows us to do things that we’ve never done before. Allowing us to control the lighting in a more active way – as opposed to a passive way – will result in true energy efficiency. One difficult aspect of LED – the speed at which product offerings change and improve – actually changes how lighting designers have to work. If my studio has a long-term project, I have to revisit all the products and instruments that we’ve specified on the project to make sure that the design is current when it is released for construction. So, although difficult, it’s positive because we’ve embraced that change as well, and believe it’s a great opportunity for us to take a last look at things. We owe it to our clients as designers to make sure we can do the best job possible.

It’s an exciting time for designers. First of all, I think there will be a number of changes. We’re going to see an advancement of onboard sensors in lighting products. The core benefit is on the networking side of the design equation – it means that luminaires are more than just light fixtures. Mesh networking, of both exterior and interior lighting, will create a lot of new functionality in our designs. I also believe that there’s an opportunity for a lighting design change – I believe we will be more integrated into building design than we ever have in the past, and the process will start at an earlier stage. This change will allow us the opportunity to make both daylighting and electric lighting part of the fabric of design, a sharp contrast to the “lighting designer as problem solver” approach. In the past, lighting designers got involved in projects after the space was designed; after the building or architecture of the interior was completed. I think that we will have a bigger impact, and that impact will be on more than just source technology, it will also bring improvement to the lighting performance of spaces.

|

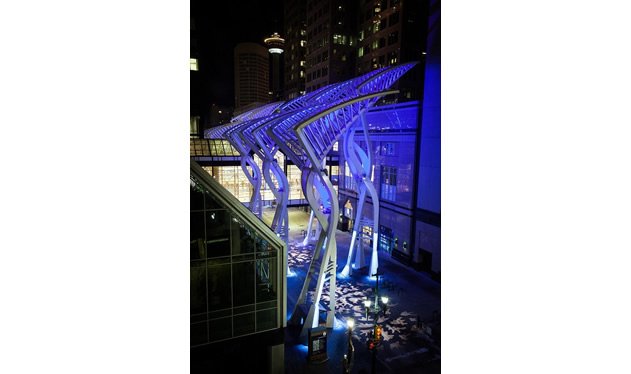

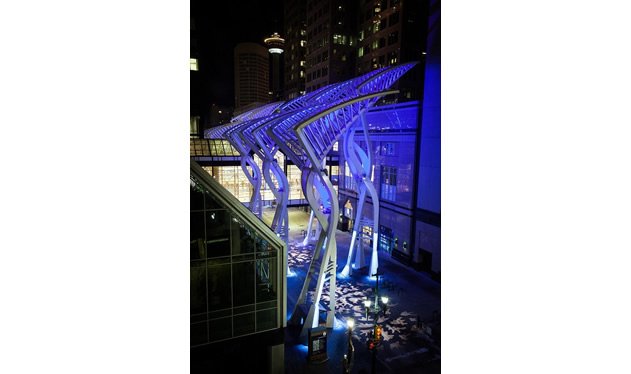

Mercier believes that luminaires will play roles that are more than lighting fixtures. Viewing the whole design as a network is the on-going trend. (Trees in the City, photo courtesy of Michael Heywood)

|

Can you tell us a bit about your new textbook, “Architecture for Light”?

Well, the development of the textbook is kind of interesting. Frankly, it actually started out as a challenge from a colleague who believed that we could no longer design interesting spaces due to code restrictions, and that we were going to be dictated by the watts per square foot of a space. We started thinking about space and volume, and the geometry and verticality that we live in right now. When we think about human evolution, the original context of a lot of lighting design was based on horizontal light levels at a time when a lot, or all, of our tasks were still on a horizontal plane. We’re no longer on that horizontal plane; we’re on a vertical plane where most of our communication is done while we’re standing up or sitting up when we’re communicating with each other. So that premise led to a particular process of design, one which will allow us to become much more efficient at designing and utilizing light where it truly belongs, in more of a vertical plane than a horizontal plane.

The textbook content is different than a traditional course because it focuses on the effect of design decisions on spaces and their ability to deliver light. It allows students to understand how vertical elements and material physics affect the lighting efficiency of a space, and help to create efficient yet interesting spaces. And it was developed to provide a lighting program that could educate interior design students and architecture students in either a full semester course or a half semester course.

You’ve commented that lighting design is both an art and a science. What does that mean to you?

I look to my past for that answer, to be honest. I’m a very technical person in some ways, although I am the creative design person when I’m at the studio. I am creative because I have this tremendous foundation of the science of illumination. I feel that it’s just like having a tool available to you. Being properly trained and understanding the science of lighting provides you with the freedom to be creative. It is what I tell my students, if they understand the foundation, they can allow their minds to be free because they don’t have to worry about whether they’re technically sound in their approach. They can look at a space, understand the client’s needs, understand human needs – for both the physical aspect of creating a functional space, as well as something that allows them to feel good about being in the space – and consider the health requirements. I truly believe that the science of illumination is the foundation, and if you have this solid foundation, you can be very creative with your approach to design.

|

|

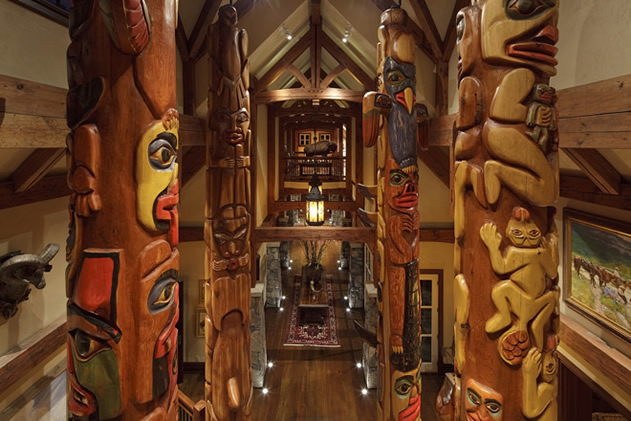

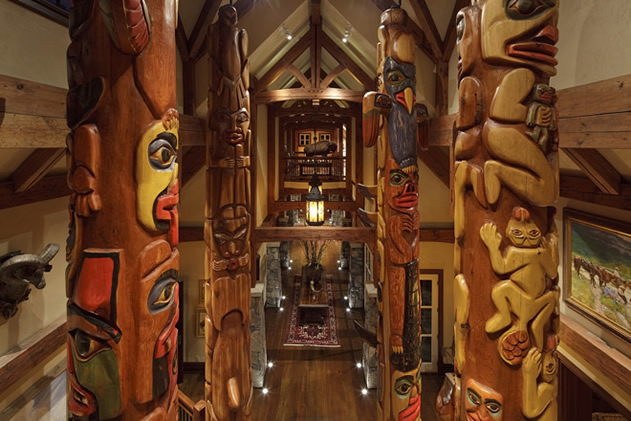

Whether it's a simple solution or that of a sophisticated one, the best lighting sedign for the architecture is the ultimate goal that all lighting designers should strive to reach. (Mountain Lodge, photo courtesy of Michael Heywood) |

When judging lighting designs, as you’ve done in the past (IES Illumination Awards, Edison Awards, etc), what are you looking for in a winning design?

I like this question because it gives me an opportunity to talk about something I believe in, which is that every space deserves the best lighting possible. When I’m looking at awards, I think the biggest challenge for almost any judge is to look beyond a project’s tremendous architecture to see whether the lighting solution was truly integrated into that architecture and actually a unique solution. Sometimes a simple solution is the best solution, and sometimes you need something that’s more complex. So, I’m looking beyond that architecture to find the lighting design concept, and figuring out if it’s the appropriate solution for the project. There are some amazing projects out there that really deserve those awards, there’s no question, but other fantastic lighting solutions occur in nondescript buildings with extremely limited budgets.

What are your most memorable projects?

There are two projects that made an impact on me; both were heritage projects that come with their own set of challenges. In the 1980s, I had my first experience in creating a highly technological space in a heritage building for the National Bank Trading Company. This building, called the Sun Life Building, was developed in the 1900s as the first office space of its kind in Montreal, and had a lot of heritage elements.

|

|

Sun Life Bldg., photo courtesy of Denis Farley |

It was the first time that I dealt with incorporating lighting instruments into the architecture so that the instruments, themselves, were not the focus. But, this challenge was a benefit to the lighting solution: it allowed us to create a space where the source and its position were hidden from the viewer allowing the space to be enjoyed for what it was, a historic piece of architecture within the city history. The project actually won an IES award, and that was my first time submitting to an award program. I keep an image of it handy whenever I need to refer back to my foundation.

The other project was the Centre Street Bridge that crosses the Bow River in Calgary, Alberta. This heritage bridge will soon be celebrating its 100th anniversary, and there was a debate amongst the community and the municipal officers as to how the bridge’s existence should be celebrated.

|

|

The Lions Awaken (Centre Street Bridge), photo courtesy of Michael Heywood |

In the end, we all agreed that instead of trying to create “architainment” through the bridge’s illumination, we would focus the lighting on the fantastic engineering and architectural elements. This was an incredible engineering solution for the early 1900s; to cross a large body of water that has a lot of movement to it, and to successfully create this bridge with concrete, well – it was an amazing feat. I really believe that every project has an opportunity to speak its own language. I’m not against the idea of applying theatrical approaches to these types of elements, it just seemed to be the right choice for this particular project, and I was very proud of it.