Hydromea, a spinoff of École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), has developed a miniature optical modem that can operate down to 6,000 meters below the ocean’s surface. It is sensitive enough to collect data at very high speeds from sources more than 50 meters away.

Radio wave can hardly work underwater as they are easily absorbed by water. So wireless internet connection underwater is nearly impossible. But it would be another story if the connection is based on light.

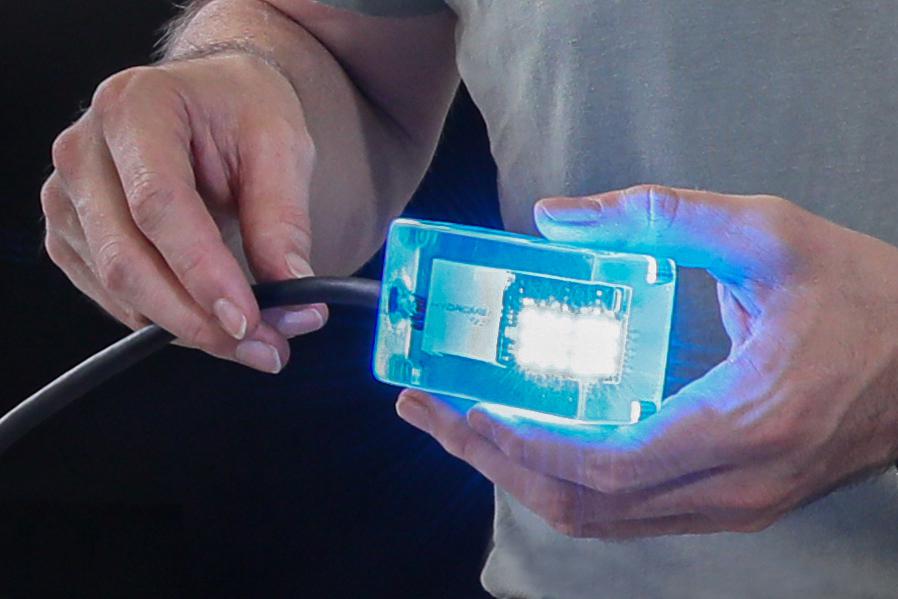

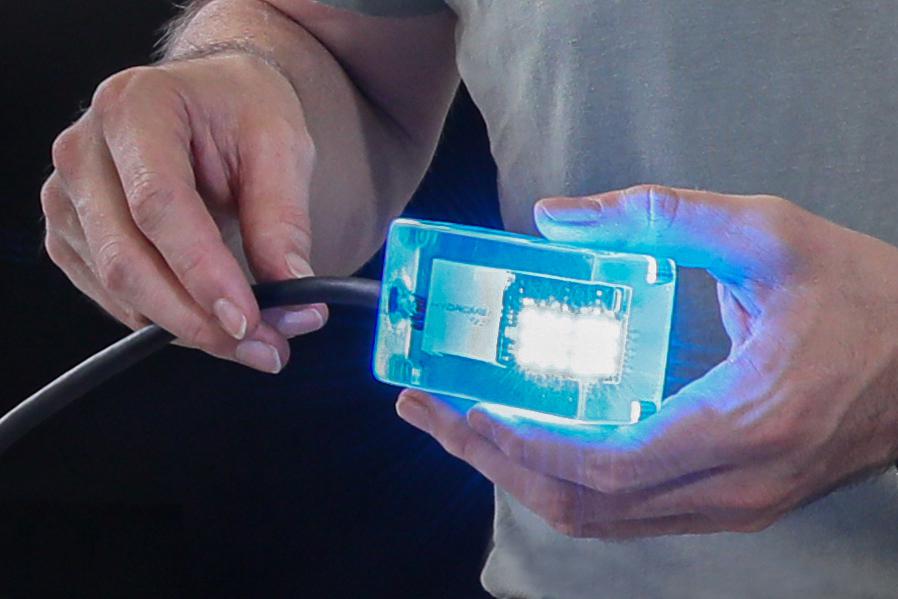

Hydromea is using light to transmit data below the ocean or lake surface. They have developed an underwater modem called LUMA that communicates through a rapidly blinking blue light. The modem converts data into light pulses that it sends out, or inversely, converts light pulses that it receives into data – all in the blink of an eye. “Our optical modem gives you a fast wireless underwater connection,” says Alexander Bahr, Hydromea’s COO.

(Image: EPFL)

“We chose blue light because even though water is generally opaque for electromagnetic waves, there is a small transparency band for blue and green light. That’s what lets our system send and receive data over long distances,” says Felix Schill, the company’s CTO. While water readily absorbs most waves, and especially infrared ones, just blue and green light can travel through it. The red and yellow light waves of the sun are absorbed in just a few meters.

The hardest part about developing LUMA was making sure it could send data over long enough distances and work reliably under all sorts of conditions. “Because light generally diffuses so rapidly underwater, finding a way to send communications over distances of 50 or 100 meters was difficult,” says Schill. “It took us a long time to develop a receiver sensitive enough to capture tiny light pulses even from far away.”

(Image: EPFL)

LUMA is designed to work at depths of up to 6,000 meters. It’s a fully contained unit in a plastic casing, which is completely encased in clear plastic so it doesn’t collapse under extreme water pressures. The system has already been tested in the Pacific Ocean, at 4,280 meters below sea level, by scientists at the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, in Germany. That’s the first research institute that Bahr and Schill began working with. “We were later contacted by companies operating offshore that were interested in our technology for laying underwater pipelines or building foundations for offshore wind farms,” says Bahr.

CN

TW

EN

CN

TW

EN