Intro: Could lighting giants’ business spin-offs marking the end of vertical integration in the industry?

Upheld as the classical business models in the LED industry, Dutch lighting giant Philips and leading German lighting manufacturer Osram business models have been the most discussed among market insiders. The two European companies vertical integration models are considered textbook cases in the industry. In contrast, many Chinese manufacturers have adopted a strategy of diversification in the industry, with the exception of ETI that has been diligently following the vertical integration creed. Since absorbing Guangdong Jiang Longda (健隆達) in 2009, through various investments ETI has been able to gradually piece together its missing links throughout the LED supply chain. The company has become a fully vertically integrated company with a comprehensive supply chain incorporating LED chips, LED packages and lighting products.

For many years, vertical integration and diversification were two parallel business models in the LED industry. Yet, in 2015 companies previously focused in the LED package market sector, such as Cree and MLS (or also known as Forest Lighting) have started to expand into downstream lighting sector, widening the scope of their vertical integration. In stark contrast, traditional lighting players including Philips and Osram have been separating key lighting businesses, and putting them up for sale. Philips for instance sold LED component business Lumileds and automotive lighting business in 2015, with further plans of selling its entire lighting business. Even Osram has parted with its light source business, which traditionally had a huge revenue stake. To a certain extent, the two global lighting giants have abandoned the vertical integration business models that they have spent years deploying and developing on the market in exchange for specialized business strategies. Hence, the emerging question is are these developments a result of paradigm shifts in the management environment, or has vertical integration become an outdated strategy?

When is the best time to implement or relinquish vertical integration?

Why is vertical integration necessary? Economists have provided a theoretical explanation a long time ago.

The advantages of using vertical integration in a fair trade market is it ensures average products can be traded on the market, while utilizing the supplier’s economies of scale in the market. Since vendors are shipping products to many clients on the market, they can lower production costs significantly, even if the procurement volume is moderate.

Yet, there are many disadvantages in a fair trade market. When the production of a particular raw material is highly used as a specific asset, than the difference between procuring the material from another supplier and in-house manufacturing becomes insignificant. In contrast, procuring raw materials from another manufacturer could even result product information leaks or being held hostage by the supplier. In other words, if there is only a single supply source for the badly needed raw material, the supplier could easily exercise control over the buyer.

In contrary, if a product sold is overtly reliant on a specific distribution channel, for instance a particular market or client, than the distribution channel resources would become a specific asset. If the company is too dependent on this distribution channel and trade from this market, and hence become limited by the distribution channel. Imagine a scenario where a large manufacturer had only a single client.

To prevent this situation from happening, manufacturers had to adapt vertical integration strategies to encourage in-house raw material manufacturing capacity through backward integration, or acquire distribution and sales capacity via forward integration strategies.

However, vertical integration strategies will become less attractive to companies, when the in-house supply chain becomes generalized, and the company can conveniently procure resources through trade. At this point, spinning-off businesses can assist companies in removing bureaucracy that has stemmed from trading internally, and refocus on core businesses. This is the primary reason behind Philips and Osram’s decision to separate their core businesses.

The complicated business relationship between Philips and Lumileds

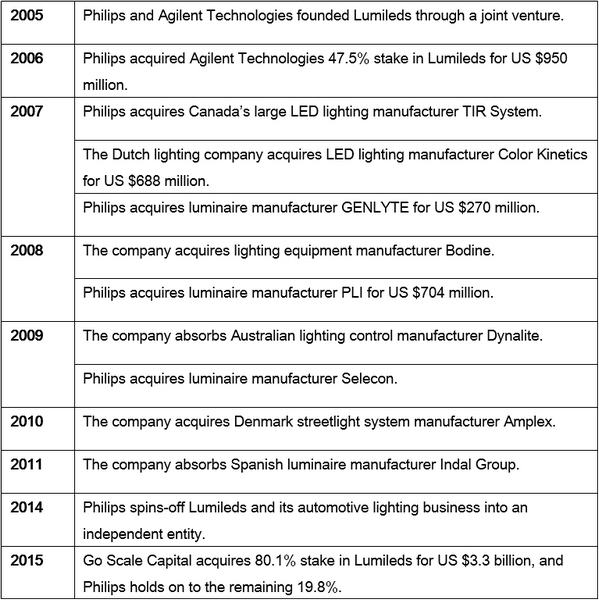

When Lumileds became a wholly owned subsidiary of Philips in 2006, the LED lighting market penetration rate remained low. Novelty and advanced technology were the characteristics of the LED industry, and Lumileds was a leader in high power LED lighting technologies at the time. Back then, Lumileds was valued less than US $2 billion.

Meanwhile, Philips did not need to procure a lot of LEDs, and there were only a handful of quality suppliers to choose from. Nichia was far ahead of the pack among Asian manufacturers at the time, with two out of three major Korean LED companies, Samsung and Seoul Semiconductors just emerging. Even after Seoul Semiconductor became a leading company in the industry, it was being hunted down by Nichia all over the globe for patent infringement. The majority of Chinese manufacturers were still imitating leading companies at this point, and were dependent on Taiwanese companies for LED chips and packages. Advanced LED technology and production capacity were specific assets for lighting companies.

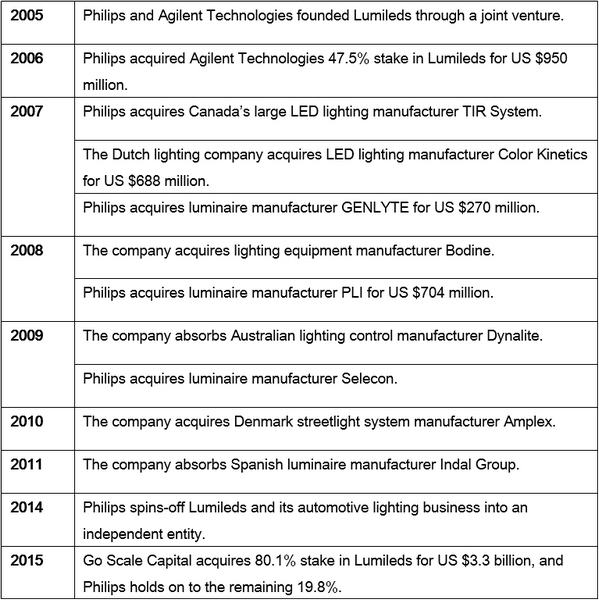

This was also why Philips needed to vertically integrate Lumileds into its internal supply chain, most importantly the move would allow it to grasp changes in the LED market. The company was able to deploy its technology and patent standards ahead of the proliferation of LEDs in the market. The company would not have achieved this by depending on the market. Besides acquiring Lumileds, Philips supported its vertical integration strategy through a series of mergers and acquisitions.

|

|

(Source: LEDinside) |

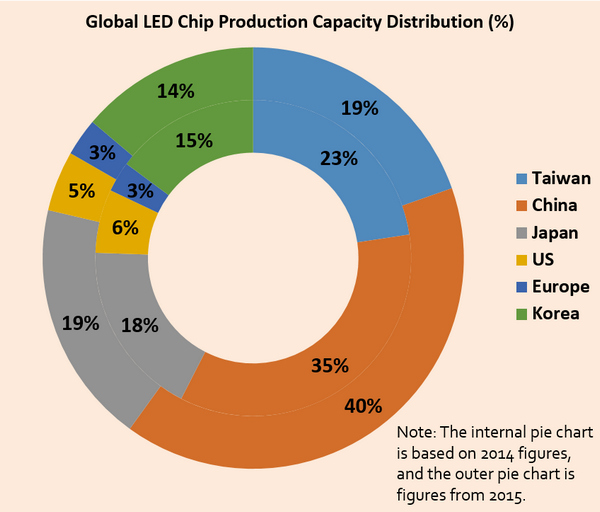

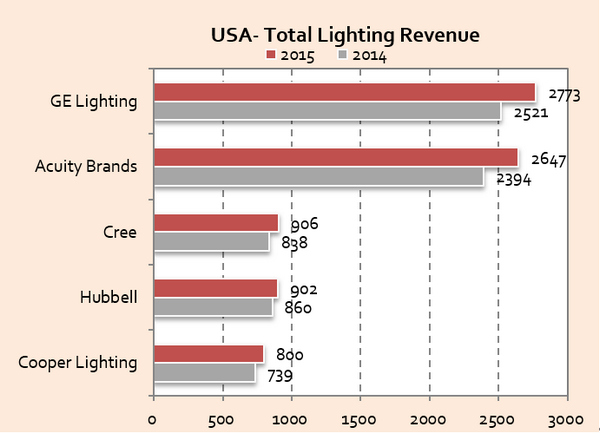

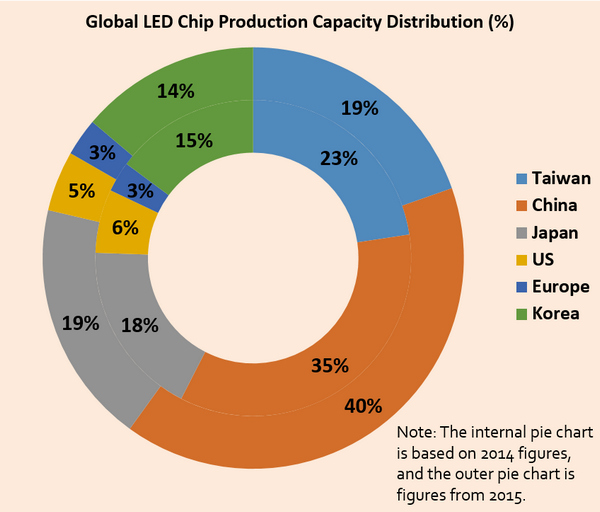

Fast forward to 2015, LED technology has matured, and the entry level barrier is significantly lowered. Chinese manufacturers have emerged as the leaders in production volume, and have close to 50% share in global LED production. This has been markedly visible in the LED chip production capacity sector, where Chinese companies production capacity peaked to 40% in 2015, while Taiwanese vendors have an even higher share of 59%. Most Chinese and Taiwanese companies have positioned themselves in diversification, and have searched for distribution channels. Hence, they have higher C/P ratio on the market, reliable LEDs or simple LED chip designs.

|

|

(Source: LEDinside Gold Report.)

|

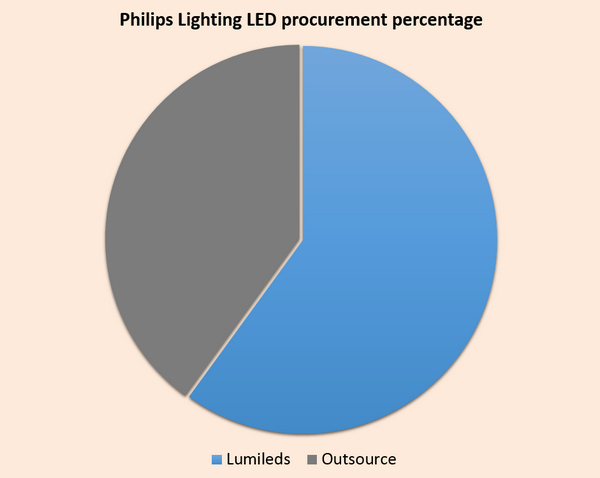

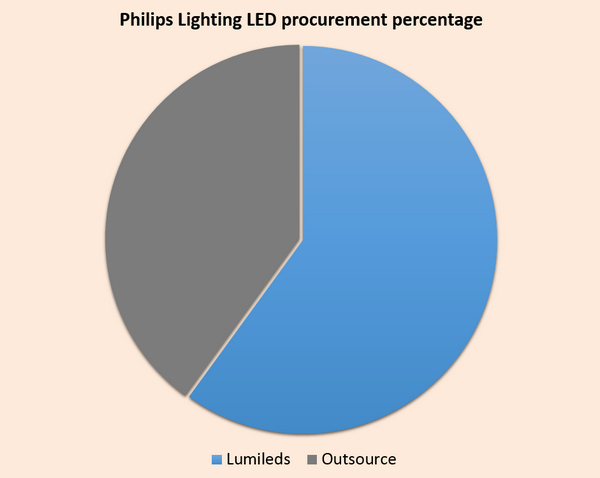

Under this new market environment, Philips Lighting had to turn to outsourcing to maintain its competitiveness, and procure raw materials and other resources from the market to lower costs, and boost its market competitiveness.

|

|

(Source: LEDinside Gold Member Report) |

In reality, Philips Lighting has been adjusting its procurement strategy. As of 2015, the company’s purchased LED ratio has reached 40%. Even LEDs brought from Lumileds are partially outsourced to Chinese and Malaysian OEMs to lower production costs. Starting from 2014, Philips LED lighting products market competitiveness soared, and along with these changes its LED lighting revenue has grown exponentially.

Under these market conditions Philips ultimately returned to its business roots by choosing lighting. Pursuing higher investment returns, Philips spun-off Lumileds, while selling its patents and brand advantages to a Chinese financial consortium led by Go Scale Capital. Lumileds estimated value at the time of its sales in 2015 reached US $3.3 billion, even without its automotive lighting department, Philips investment return in Lumileds had more than doubled over the last 10 years.

From the supply chain perspective, Philips Lighting’s LED procurement has allowed it to speed up its commercialization model, while raising its external resources. Philips held on to a 20% stake in Lumileds after its sales, due to its strategic value and role as an important supplier.

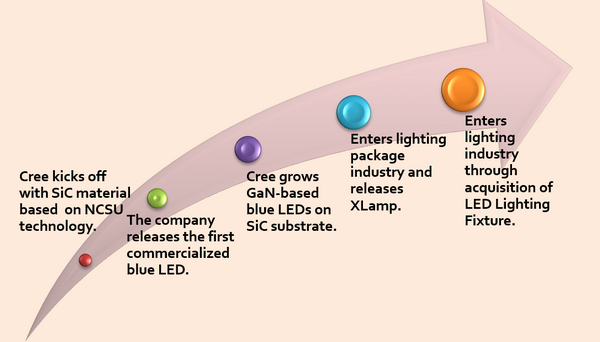

Osram courageously parts with founding business lighting to survive

In April 2015, Osram announced it would be splitting its less profitable general lighting businesses into an independent entity, or consider selling it off. The move was to assist Osram to direct its resources to automotive lighting and its LED component business. The announcement came just two years after Osram was spun-off from Siemens.

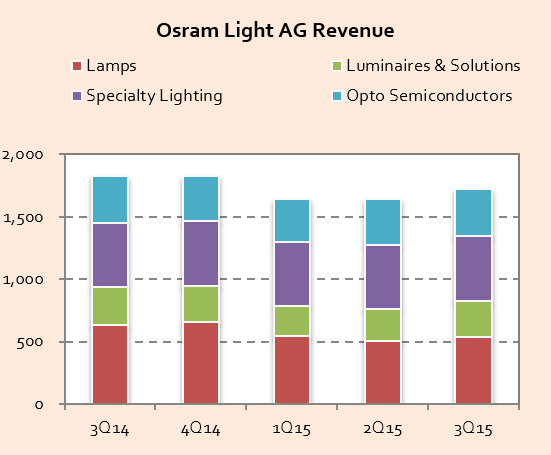

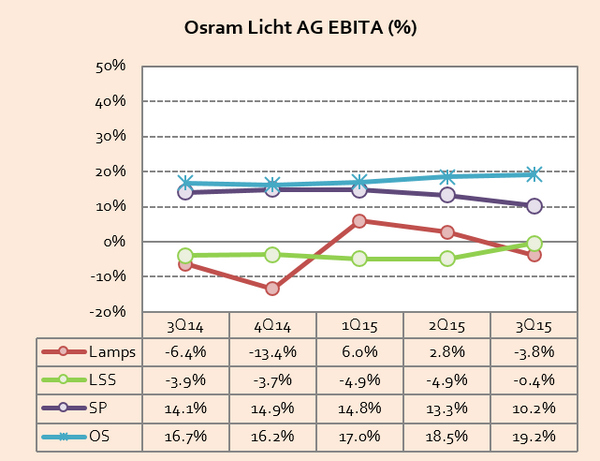

The businesses being separated from Osram include its Classic Lamps and Ballast (CLB) and LED Lamps and Systems (LLS), which account for 40% of the company’s revenue. According to the company’s 2014 fiscal report, these businesses revenue was down 15% to EUR 1.96 billion (US $298.02 million) compared to 2013, and its Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITA) had fallen below the average of 4.6%.

Following the spin-off, Osram will keep its specialized lighting, automotive lighting, LED components and Osram Opto products. The less profitable general lighting business will also be sold. Shortly after the announcement, Chinese manufacturers showed strong interest, of not in the German company’s production capacity, but in the century-old super lighting brand.

|

|

Osram's brand development. (Osram/LEDinside) |

Osram was founded in 1906 by Deutsche Gasglühlicht-Anstalt (also known as Auer-Gesellschaft). The company earned its reputation as a global brand by manufacturing two materials used by incandescent lamps, Osmium and Wolfgram. Thirteen years later on July 1, 1919, the company was renamed OSRAM Werke GmbH Kommanditgesellschaft. In the same year, Auer-Gesellschaft, AEG and Siemens & Halske integrated their light source departments to form Osram. In 1976, GE sold its stake in Osram to Siemens. Siemens would go on to complete the business transactions for acquiring GE’s stake in Osram two years later, and became the German lighting company’s sole shareholder. This also marked the beginning of Osram’s transition into a wholly-owned subsidiary of Siemens.

In Osram’s century long history, it was one of the world’s largest bulb factories at one point, manufacturing a third of the world’s bulbs. Some people have even summed up Osram’s history into the simple phrase “Osram is a bulb manufacturer.” However, the company has emerged into a multinational enterprise today, becoming much more than just a bulb maker. It is no exaggeration in saying Osram’s general lighting business and brand, which has been passed on for generations has been its founding asset.

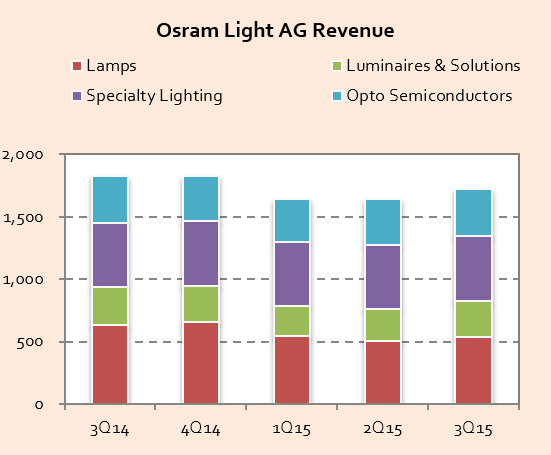

|

|

Osram Light revenue. (Source: LEDinside Gold Member Report) |

So why would Osram sell its lighting business and brand?

An observation over the past years of Osram’s product revenue structure reveals globally LED lighting has been rapidly replacing traditional light sources. Although, Osram intends to enter the LED lighting business, it has positioned its LED business in the mid to high-end market. This has limited the support of its LED end-products, and has made it difficult to compete against the tsunami of low-priced products being released by Asian companies. Even Philips has been more flexible than Osram in the lighting replacement tide. The Dutch lighting company has utilized its global distribution and brand advantages, secured global export markets, and fully mobilized its cost advantages in the Chinese supply chain to defend its global leadership position. In contrast, Osram has been ambushed in this revolutionary changes, and over the last few quarters its lamps and LSS products EBITA dipped into the red several times, and have continuously declined in the last three quarters.

|

|

(Source: LEDinside Gold Member Report) |

So should companies sell businesses once they incur losses? The logic is not that simple. The real reason is the automotive lighting business has been Osram’s LED business main revenue and profit source. The synergy effect between the German company’s lamps and LED businesses has been relatively low. In other words, the LED lamps businesses brand and distribution channel is not an essential diversification asset for Osram. The company would be able to have a better LED end-product export solution through distribution channels or markets. Hence, separating the business has been the best option, and it has been easy for the company to select the business it wants to keep. Osram Semiconductor’s profits and market outlook has been far more valuable than the100-year-old mature traditional lighting market.

Moreover, Osram could strengthen its core businesses through funds received from selling its general lighting business. This was also the reason that Osram announced it would be investing EUR 3 billion (US $3.27 billion) in white LED chip R&D and building a new fab in Malaysia in late November 2015, it would be a logical move after selling its lighting business. The company preferred to part with its less profitable businesses and direct resources to profitable projects and businesses, than maintain a façade of a comprehensively vertically integrated business, while pumping resources from its profitable departments to those that incurred significant losses. Osram should be applauded for its courage in implementing this business strategy that probably resulted from accumulated wisdom it gained over the last century.

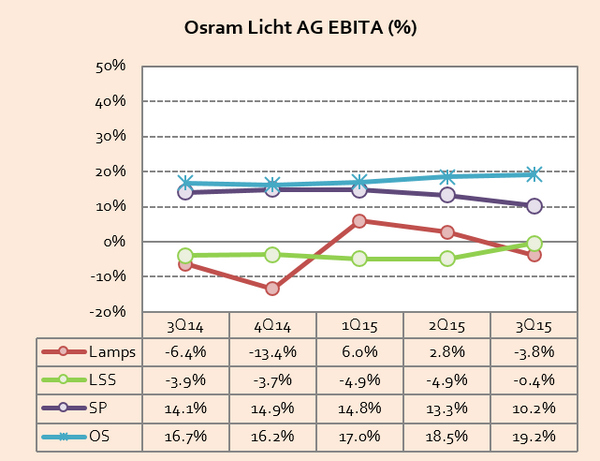

Cree loses its way in the maze of vertical integration

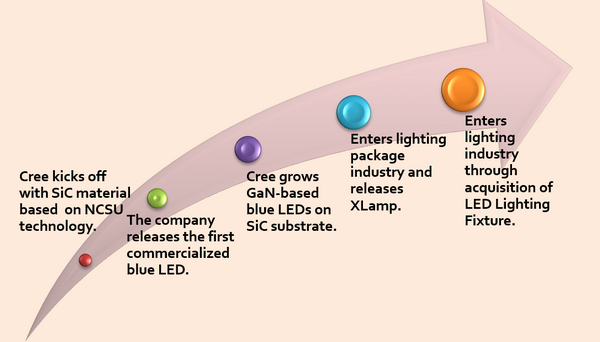

Cree is with no doubt the epitome of vertical integration in the LED industry, from SiC material advantages to vertical LED chips, to record holder of luminous efficacy. The component manufacturer has been the leading lighting brand in the U.S., and has an entirely different development path from sapphire substrate based LED companies.

Due to its limited compatibility with mainstream technology, it has been difficult for Cree to completely rely on market trade as its main distribution channel. Since Cree started selling LED chips, clients have admired its high luminous flux and reliability. However, the U.S. company has been the only vertical chip maker in the market, which has made it difficult to promote its products. This is mainly because no manufacturer wants to be tied down by a single supplier. Shortly after becoming a LED chip supplier, Cree ventured into the vertical integration LED package manufacturing.

Cree’s vertical integration road map

|

|

Note: NCSU in this infograph refers to National Carolina State University (NCSU). (LEDinside) |

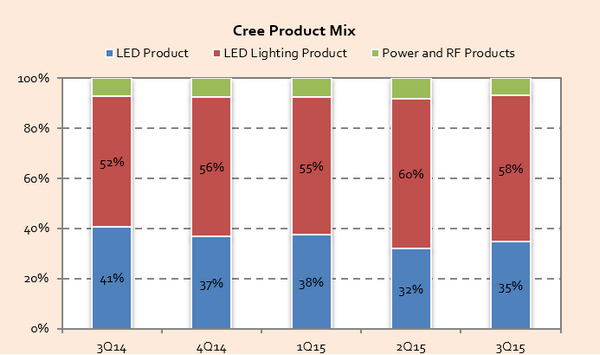

This strategy proved to be effective, Cree’s outstanding LED power technology, and ultra-high luminous efficacy quickly propelled its global ranking to the world’s top five LED manufacturer. However, incompatibility with mainstream technology continued to plague the company, even though Cree’s clients were able to acquire market shares because of the chips high brightness during the industry’s early phase, as the market expanded clients sensitivity to technology advantages started to drop. When product prices became the center of market competition, Cree encountered a potential crisis of losing price sensitive clients. Hence, Cree once again strongly promoted vertical integration strategies as it paved its entry into the lighting market.

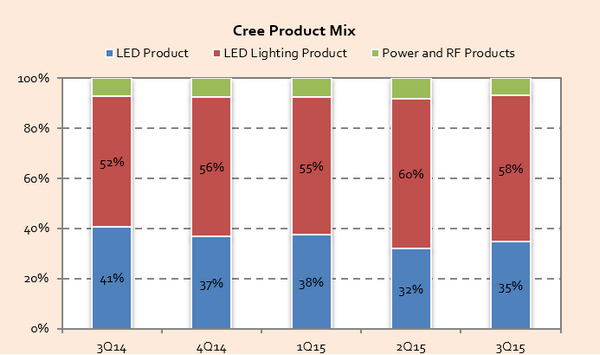

|

|

Revenue shares of Cree's product mix. (Source: LEDinside Gold Member Report) |

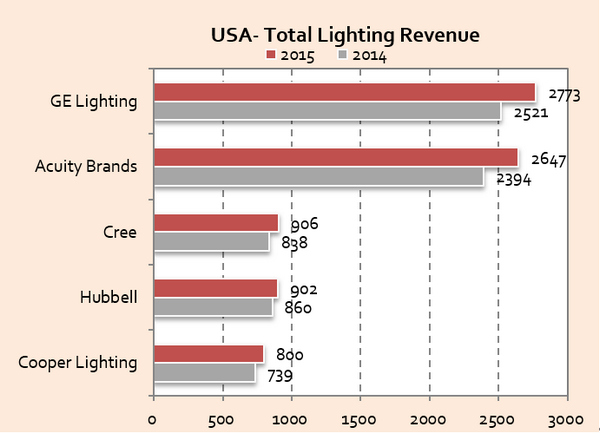

In fact, it has become unsuitable to classify and position Cree as a LED company, instead it should be reclassified as a lighting company. From the last few quarters, Cree’s lighting products revenue share exceeded 50%, and in North America the company’s rankings has risen to become the third largest manufacturer.

|

|

(Source: LEDinside Gold Member Report) |

The interesting part about Cree’s strategy is whenever a client chooses it as a supplier, it faces the potential risk of being suppressed by it. We know that exposure to default risk is one of the main trade costs. For clients to willingly choose Cree, there needs to be enough potential benefits to compensate these risks. The benefits can be technology advantages or enormous cost advantages, but if these two conditions cannot be met, than the best strategy for logical clients is choosing a supplier with more standardized products. From this aspect, vertical integration has become a necessity for Cree.

But there is a catch. The risks associated with vertical integration is stepping into client’s business territory, with conflict of interests becoming unavoidable. Hence, clients that acquire market advantages by using Cree’s bright LEDs will become the first to be directly impacted by its vertical integration strategies. These clients are required to reposition themselves on the market, which is one of the reasons why Cree’s LED revenue has contracted in recent years.

When Philips and Osram abandoned their original markets, and vertical integration strategies, Cree has been the only one to stick to the strategy that has transformed it into a lighting brand. The company has continued to manage competing lighting and package markets, which will continue to create issues for the company.

(Author: Figo Wang, Senior Analyst, LEDinsidehttp:// Translator: Judy Lin, Chief Editor, LEDinside)

Related article for further reading: