The on-going development of LED research and bioelectronics medicine has sparked off a new solution for curing bladder problems. A team consisting of researchers from Washington University School of Medicine, the University of Illinois and Northwestern University has created an implantable device with biointegrated LEDs that can detect and tamp overactivity in the bladder.

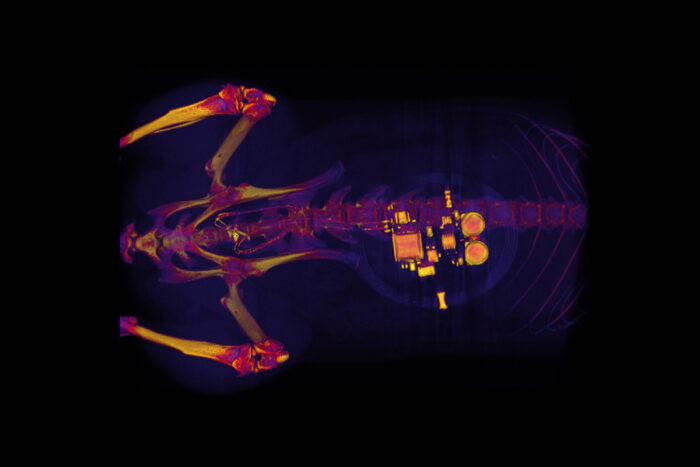

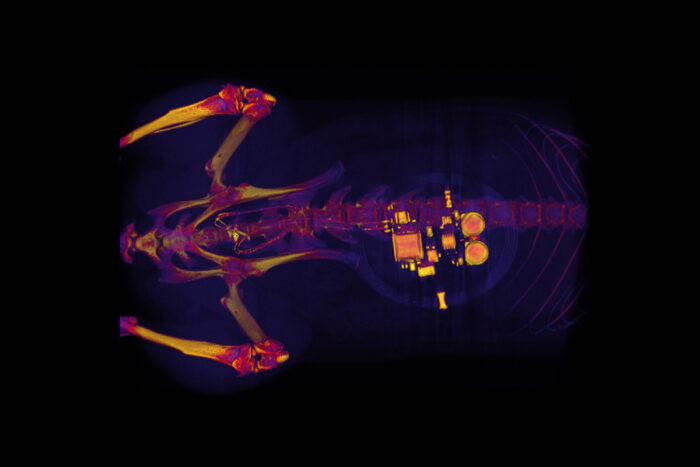

The research team of neuroscientists and engineers introduced a miniaturized bio-optoelectronic device that is soft and stretchy and implanted it around the bladder of the lab rats. The device expands and contracts as the bladder fills and empties. The researchers also inject proteins called opsins into the animals’ bladders. The opsins are carried by a virus that binds to nerve cells in the bladder, making those cells sensitive to light signals. Then the researchers are able to use optogenetics — the use of light to control cell behavior in living tissue — to activate those cells.

(Image: Washington University School of Medicine)

The device detects activities from the cells in the bladder and transmits information via blue-tooth communication to an external hand-held device. The scientists can read and process the information in real time with a simple algorithm which detects when the bladder is full or empty and notifies when bladder emptying occurring too frequently.

“When the bladder is emptying too often, the external device sends a signal that activates micro-LEDs on the bladder band device, and the lights then shine on sensory neurons in the bladder. This reduces the activity of the sensory neurons and restores normal bladder function,” said Robert W. Gereau IV, PhD, of Anesthesiology at Washington University School of Medicine.

With the result, the researchers aim to develop an autonomous implantable system integrated with biophysical sensor, battery-free module and data analytic algorithms that can operates synchronously with the body and delivers therapy when detecting problems.

Gereau and the team expect to test similar devices in larger animals and believe that a similar strategy could work with people.

The results of the study were published in Nature in January 2019.