|

|

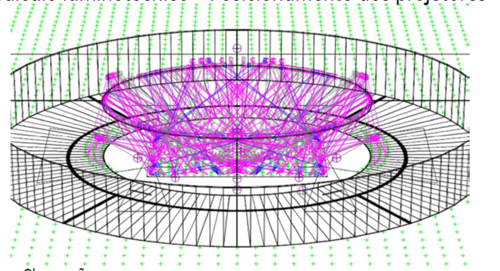

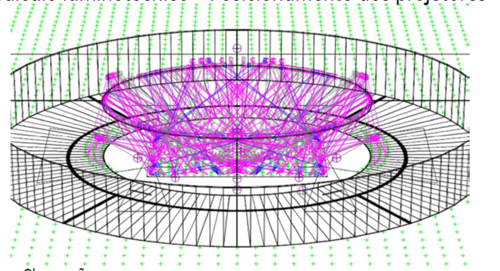

The Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro. (Photo Courtesy of GE) |

When soccer teams from Brazil and Croatia run out on the pitch in São Paulo on Thursday afternoon, they will kick off one of the biggest sporting events in history, according to a latest GE blog entry. The cumulative television audience for the world’s largest soccer tournament is estimated to top 3 billion. The final at Rio de Janeiro’s Estádio do Maracanã on July 13 could be one of the most watched TV broadcasts in history.

For the first time, all of the tournament’s 64 matches will be televised in ultra-high definition, which requires an average 34 cameras per game, and GE is helping make the pictures pop. The company designed and installed high-tech lights that illuminate the pitch at five of the 12 tournament stadiums, including the Maracanã.

|

|

Top and above: The Maracanã stadium in Rio de Janeiro.(Photo Courtesy of GE) |

The lights’ optics and tight focus eliminate shadows on the field. They also generate high-intensity light near the natural spectrum so that the Brazilian national jerseys will truly look canary yellow on the green grass. “We would be in trouble if they looked orange,” says lighting engineer Sergio Binda, who works as a marketing director at GE Lighting Latin America. “The light must look authentic. Fans around the world should feel like they are in the stands when they turn on their TVs.”

|

|

Workers placed 396 GE EF 2000 projectors along Maracanã’s roof, 121 feet above the field, to obtain the best light level and uniformity.(Image Courtesy of GE) |

|

|

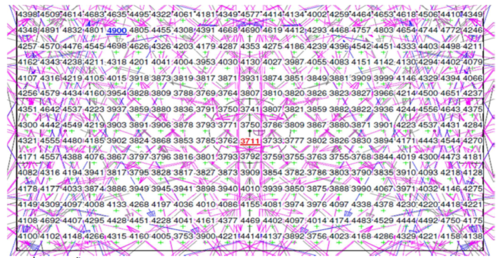

GE engineers calibrated Maracanã’s lights on a grid of 315 points 10 inches off the field and 5 by 4.5 meters apart.(Image Courtesy of GE) |

The lighting team worked closely with scientists at GE Global Research to develop precise and highly efficient flood lights that make colors look natural. “Light is electromagnetic radiation and each color corresponds to a specific wavelength,” Binda says. “We see colors when those wavelengths bounce off a specific surface, like a jersey. But if your light source does not generate, say, a true red wavelength, then it can’t bounce off and you won’t see that color on the jersey.”

|

|

Arena da Amazônia in Manaus, a city deep in the Amazon rainforest, will see action for the first time on Saturday when England plays Italy.(Image Courtesy of GE) |

The lights that GE installed at the stadiums use electric metal halide lamps that emit light very close to the near-perfect white light produced by incandescent light bulbs. But they are much more efficient and durable.

Each fixture holds a reflector with a mirror-like aluminum coating and a special glass lens that trains the light beam on a specific point on the pitch. “The lamp and the optics are the secret sauce,” Binda says. “We use special software to achieve the best geometry and increase the intensity of the lamp.”

|

|

Arena Pernambuco is located in Recife in northeastern Brazil.(Image Courtesy of GE) |

Each of the five stadiums - besides Maracanã they include arenas in Porto Allegre, Brasília, Manaus and Fortazela - has about 400 lights. It takes about three days for GE workers to focus them on the field. They tune two lights at a time, one from each side. They train them at a point on a special matrix superimposed on the field and then measure their output with a handheld luminometer. “It’s almost a perfect lighting down there,” Binda says.

GE lighting will also light interior spaces at the National Stadium in Brasília and the Amazonia Arena in Manaus.

|

|

A worker is measuring light intensity with a luminometer on the field of the National Stadium in Brasília.(Image Courtesy of GE) |

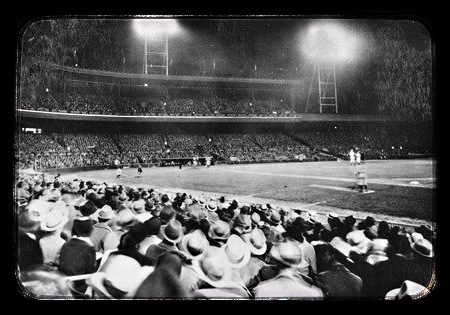

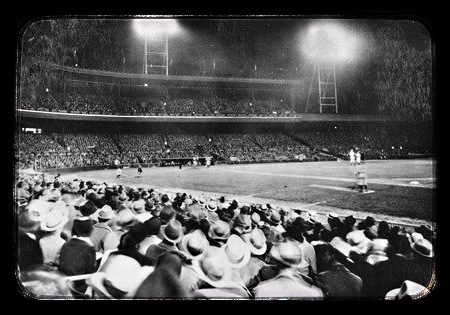

GE is an old hand in sports lighting. In 1927, GE lights illuminated the first night game ever played in Major League Baseball. On Friday, May 24, 1935, a crowd of 20,000 people watched the Cincinnati Reds beat the Philadelphia Phillies 2-1.

|

|

(Photo Courtesy of GE)

|

CN

TW

EN

CN

TW

EN